- It is the world’s largest civil society organisation focused solely on water, sanitation and hygiene (WaterAid, 2015)

- Since WaterAid started they have successfully reached over 25 million people with clean water, 25 million people with decent toilets, and over 18 million people with good hygiene (WaterAid, 2015)

but I didn’t really know about the organisation beyond fundraising, who they actually are. This article is my research on WaterAid, in preparation for a visit to the WaterAid UK HQ in London as part of the Institute of Water Rising Stars Programme.

Overview

WaterAid is an international not-for-profit non-governmental organisation set up in 1981 as a response to the UN International Drinking Water Decade, a ten-year period 1981-1990 designated by the United Nations to bring attention and support for clean water and sanitation worldwide (WaterAid, 2020a).

It has seven member countries in the UK, US, Australia, Sweden, Canada, Japan and India and operates in 28 countries to provide clean water, decent toilets and good hygiene (WaterAid, 2020b). All of these federation members are independently constituted organisations with their own boards (WaterAid, 2019a).

|

| WaterAid (2019b) |

Within the UK, in the London office, there is a Chief Executive and a team of five Directors, an Internal Audit and Compliance Department and the Secretariat for WaterAid international. The Directors are responsible for the Departments of International Programmes; Policy and Campaigns; Finance and Information Technology; Communications and Fundraising; and People and Organisational Development (WaterAid, 2019a).

Even the symbol for WaterAid consists of the sign for water

(Sherrard, 2020).

Goals and Challenges

There are four main goals (or principles) of WaterAid (WaterAid, 2020c):

- “Principle 1: Global interest. Achieving WaterAid's mission as effectively as possible is fundamental to all we do and global interest is paramount.”

- “Principle 2: Subsidiarity. WaterAid international will only undertake activities that it can and will deliver more effectively than WaterAid member countries.”

- “Principle 3: One country, one WaterAid. WaterAid will only have one delivery organisation in each of the regions or countries where services are provided.”

- “Principle 4: Sustainability. The members of the WaterAid federation will be organisations that are, or are expected to become within a reasonable time-frame, self-sustaining and able to contribute significant resources to the delivery of WaterAid's strategy.”

The largest worldwide challenges that WaterAid have stated are (WaterAid, 2015):

- Rapid urbanisation, population growth and economic development

- Public health

- Climate change

- Financing

- Social and economic inequality

- Sustaining water and sanitation services and good hygiene behaviour

And, specifically, WaterAid UK reported that in 2018-2019 their biggest risks were (WaterAid, 2019a):

- Brexit, global recession and/or scarcity of funds in the market

- Reputation of charity sector

- Constrained political environments

- Terrorist attack

Changing Policy

One thing I thought was interesting is that WaterAid are also tackling wider problems, such as anti-microbial resistance, by participating in a global meeting on the topic, the Second Global Call to Action on Anti-Microbial Resistance (WaterAid, 2019b). They also have the ability to influence national policies, strategies or standards, with 15 of these influenced in 2018 (WaterAid, 2019a). I was especially interested in how WaterAid change policy, having read UK, EU and WHO policy in the past.

The key way in which WaterAid actually work is through a partnership basis, it is not

telling people what to do. It is the local partners that do the work, not WaterAid themselves (Laird, 2020). And this, too, is how WaterAid alter policy.

Water Aid change legislation very informally, on a case by

case basis. They do this by creating a guide, such as Female Friendly Toilet,

then approaching the local authority with this guide (Kimbugwe, 2020). They say that the thing that drives real changes is getting the masses, the people, to care, like

the work of David Attenborough and Greta Thunberg which has inspired people and

eventually ended in political changes such as the Climate Change Summit 2020, a

summit in preparation for the UN Climate Change Conference 2020. At this event,

Water Aid attended to bring the people element, reminding attendees that the

most important use of water is for people to drink, rather than industry or for

power (Laird, 2020).

Uganda: A Case Study

So, I've touched on the aims and challenges of WaterAid but how do they actually achieve these goals and mitigate these challenges? During my WaterAid visit, I was lucky enough to meet Ceaser Kimbugwe, who provided insight into some challenges surrounding water and sanitation in Uganda and one way in which WaterAid has helped the situation. This case study has been written and is informed by the personal communications of Ceaser Kimbugwe (2020).

Schools used to have pit latrines but some are now moving to water-fed toilets. However, because of the political climate surrounding water, schools are billed for their water use and since the shift, public schools may be unable to pay their water bills. WaterAid have helped the situation by designing toilets that are more water efficient.

Finance

So, I've touched on the aims and challenges of WaterAid but how do they actually achieve these goals and mitigate these challenges? During my WaterAid visit, I was lucky enough to meet Ceaser Kimbugwe, who provided insight into some challenges surrounding water and sanitation in Uganda and one way in which WaterAid has helped the situation. This case study has been written and is informed by the personal communications of Ceaser Kimbugwe (2020).

In Uganda there is a single utility that covers everywhere

but has only an 8% sanitation coverage. There has been a 5.4% growth in

urbanisation due to rural to urban migration and on a day-to-day basis, the

population of Kampala is 5 billion in the day and 1.5 billion at night because of

people coming to the city to work.

The water industry in this area is very political, with

domestic water tariffs increasing to cover a decrease of industry tariffs to

help increase industrial growth. This is despite the fact that sometimes,

especially if it is due to roadworks, the water supply can get cut off without

notice, sometimes for up to 5 days.

In some areas there is one pit latrine for 15 houses, with

each house containing 6 people. Manual emptying of the pit latrines is

completed at a cost of ~6$ for a full ~48l latrine. Due to this cost, people choose

to let them fill to the brim, rather than the advised 2 feet from the brim, and

do not empty their latrines completely, meaning the fill quicker.

Some people receive tokens for subsidised water tariffs but

instead choose to use local streams as they are free, meaning they can sell on

their tokens. These streams look clean but are actually surrounded by these

overly filled unlined pit latrines, meaning it is faecally contaminated. Even

if people are aware of this and so boil this water before consuming, they may

still use it for other purposes without boiling it, such as washing clothes,

which can lead to a public health risk itself.

Schools used to have pit latrines but some are now moving to water-fed toilets. However, because of the political climate surrounding water, schools are billed for their water use and since the shift, public schools may be unable to pay their water bills. WaterAid have helped the situation by designing toilets that are more water efficient.

Finance

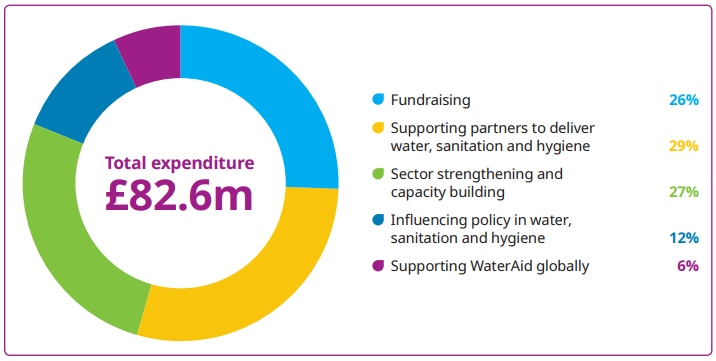

One thing people are very interested in about WaterAid and other similar charities is their finances. The most simple way to show the WaterAid finances is through a series of images from the UK Annual Report and Financial Statement 2018-2019 (WaterAid, 2019a).

One thing that I had not thought of before was Water Aid and

their corporate partnerships. Sales of a product increase by 16.3% or more when

the Water Aid logo is added. For instance with Water Aid branding, 19% more

packs of Andrex were sold, which, over a year raised ~£300,000 for Water Aid.

These partners generally do a 3 year trial that can then by extended, for

instance, HSBC have now been a sponsor for 7-8 years (Piravano, 2020).

References

- Kimbugwe, C. (2020), Personal Communications.

- Laird, P (2020), Personal Communications.

- Pirovano, R (2020), Personal Communications.

- Sherrard, C (2020), Personal Communications.

- WaterAid (2015), Our Global Strategy 2015-2022, https://www.wateraid.org/uk/our-global-strategy, Report

- WaterAid (2019a), UK Annual Report and Financial Statement 2018-2019, https://www.wateraid.org/uk/our-annual-reports, Report

- WaterAid (2019b), Global Annual Report, https://www.wateraid.org/sites/g/files/jkxoof271/files/wateraid-global-annual-report-2018-2019_2.pdf, Report

- WaterAid (2020a), Our History. https://www.wateraid.org/uk/our-history, Website (Accessed: 09/03/20)

- WaterAid (2020b), Where We Work, https://www.wateraid.org/where-we-work, Website (Accessed: 09/03/20)

- WaterAid (2020c), How We're Run, https://www.wateraid.org/how-were-run, Website (Accessed: 09/03/20)